Soterios Gardiakos

Soterios Gardiakos was born in Kalamata, Greece on January 12, 1944 but moved to the U.S.A. with his parents, brother and sister in 1952 when he was eight years old. The family lived briefly in New York City and than moved to Detroit, and on to Chicago in 1959 where he lived until 1992 when he moved to Aurora Illinois, where he presently resides.

Sometimes people tell me that my father has an accent; I tell them it must be a Detroit one.

Soterios started sculpting in clay in Detroit where his art teacher wanted him to go on to special art classes in the afternoons, after school. He also did some clay sculpting in Chicago where, unfortunately, only one piece survived; that being number 23 in this catalog titled Dachau, where many Greek prisoners where interned during the German occupation of Greece during World War II.

Soterios was always fascinated by astronomy and space travel and in 1956, he organized the Rocket Squad, a club of like minded friends that built and launched home made rockets. In 1959 they were disappointed when the Russians beat them at putting into orbit the first man made satellite, Sputnik I. He has always been an avid science fiction fan as well. It was this interest which caused him to strike the Apollo 11 medal under a commission from the Capitol Bank of Chicago with the help of his friend Alex Efthymiou and the president of the bank Mr. Scandiff. Apollo 12 was commissioned by Harco, which also distributed the three books he has written on Numismatics, a company owned by the numismatist Harold Cohn. In 1971 the Capitol Bank of Chicago, owing to the large number of its Greek customers commissioned Soterios to strike the Kolokotronis (a relative of Soterios) medal celebrating the 150 th anniversary of Greek Independence from the cruel yoke of the Turk. Special permission was granted from the Secretary of the treasury (which was required at the time) to strike two to three medals of each in gold for presentation purposes.

His father was a Watchmaker and a jeweler, who loved to create and build clockwork-like mechanisms. Soterios was fascinated with the casting of Jewelry, especially with the unlimited use that wax could be put to. In 1962 using his father’s wax, he made Herakles (No. 4) which was not cast until 1987, the year he bought more wax from John Keith who cast all the sculptures from number four to number forty seven. He started working earnestly with wax from 1987 to 1990 when he abruptly stopped.

In 1989 (October 28 to November 26) Soterios had his first gallery showing with the Great Lakes Chicago gallery. It was a very successful showing and to his surprise, not mine, several sculptures were sold. His second showing was at the International Art Traders Gallery which also went well. He does not remember the name of the third Gallery..

In 1991 the ISC’s, (International Sculpture Center) Sculpture Source, the most advanced resource for contemporary sculpture picked Soterios’ number fourteen, two kores, one of nine, for their advertising campaign promoting contemporary sculpture out of over 9,000 sculptures in their archives.

In the mid 1990’s he made 4 wooden sculptures, number forty eight to fifty one and again stopped abruptly. Number 49, Heracles and Antaeus was painted by his daughter Alexandra.

In the 1960’s Soterios was a tool and die apprentice and loved working in machine shops and foundries. He was especially awed by the large industrial machines of International Harvester located at the time on 26 th and California, Finkl steel company Located on Armitage Ave. and the Pettibone Company located on Cicero and Division streets, all three located in Chicago. From there he went to other business ventures not related to industrial machinery. He founded U.S. Graphics, Unigraphics Inc. and Obol International, the later been a publishing company primarily publishing books on numismatics and art. But in his mind he had always wanted to work once again with machine tools; he loved and missed the feel of metal.

Around 2000, he started collecting early commercial use movie projectors and as parts could no longer be ordered from the factory (the earliest projector in the collection having been made by Thomas Edison in 1896) Soterios started buying industrial machines to make new parts and repair damaged parts for these rare projectors. He has written five books on these early movie machines. Using these machines in 2004 he once again started work in earnest in a style and in materials unlike any he had done before constructing his first piece, number 52 in the Industrial Expressionism series and is continuing this work while running several business ventures at the same time.

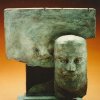

The earlier pieces were inspired mostly by ancient Greek mythological themes, as Soterios among his other attributes is an avid amateur historian of the classical Greek civilization, and the surrounding area. He prefers to use commercial grade metals and his castings in these later work use commercial grade techniques rather than the lost wax process.

The second series is inspired by the magnificence of the American Indian totem pole and its form. In particular, the universal and philosophical severity of its form gave him much inspiration.

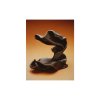

The third series is a complete abstract manifestation of the artists’ Industrial expressionism. The shapes are created not to be used as metaphors of something that once was. There is no sacred story being represented in this series; the mythos starts when you look at them and ends when you stop thinking of the art. They aren’t in reference or in context to anything. None of his works are welded, for at the present, he doesn’t wish to “mar” his work. Instead, everything is held together using pins and bolts.

Soterios is opposed to over representing within his art. An abstract idea doesn’t need to over identify with every day forms. That would be a caricature of the conceptual. It would be as insulting as putting a mustache on a Mondrian. It is art that doesn’t require the representation of the human shape, but isn’t depending on pretense to carry it through. It is art that celebrates the intangible joys and woes of being human through it’s every sharp austere line to it’s ever-devouring voluptuous curves. All one has to do is look at it: It is visual, it is industrial, it is expressionism.

Chryssafenia Gardiakos